Usually every week I come across an article or narrative on creativity, its many facets and how better to utilize one’s own creativity. Such is the case this week.

One of the subscriptions I maintain (zero cost, but there is an option for minimal cost) is with Medium. I’ve even posted some of my writings on the site.

This week I came across a posting having to do with noise and the role it plays in creativity. It was written by Donald Rattner, Architect, and since it has some very interesting points, I’d like to share it with you. . .

. . .Maybe it was inevitable, but after years of touting the virtues of the open workspace, people who plan and use them appear to be having second thoughts about its effectiveness. Among the biggest drivers behind the mounting backlash are complaints about noise, especially in the form of overheard conversations, ringing phones, and clattering machines.

But before you jump on the “silence is golden” bandwagon, it might be worth taking a step back to assess the problem with a cooler, more objective eye, especially if you spend some part of your day in creative problem solving. The reason? A modicum of noise has been found to boost idea generation, rather than interfere with it.

Noises Off or Noises On?

Credit a team of researchers drawn from several different universities for daring to challenge status quo thinking.

In 2012, the trio published a paper documenting a series of lab experiments they ran to study the effect of noise on creative task performance. Their methods were pretty straightforward: Subjects performed various exercises designed to measure ideational fluency and open-mindedness while a soundtrack played in the background.

The track played at either a low (50 decibels), middle (70db), or high volume (85db). A fourth group performed the same exercises without any accompanying soundtrack to establish a baseline from which to measure the collected results.

Contrary to expectation, the people in the quiet sessions did not achieve the top scores. That honor went to subjects exposed to midlevel noise (70db).

As a point of reference, 70db is the rough equivalent of the din at a bustling restaurant or coffee shop. It also approximates the loudness of a running shower, which is probably one reason why we so often get good ideas while under the spigot.

It’s evident from the data that the right type and level of noise can literally change the way our creative minds work. But how? And why? And how do we harness this information to boost our creative output in real-world settings?

Guilford’s Model of Creative Thinking

A model of creative thinking first developed in the 1950s might be the most effective vehicle for providing answers to these questions.

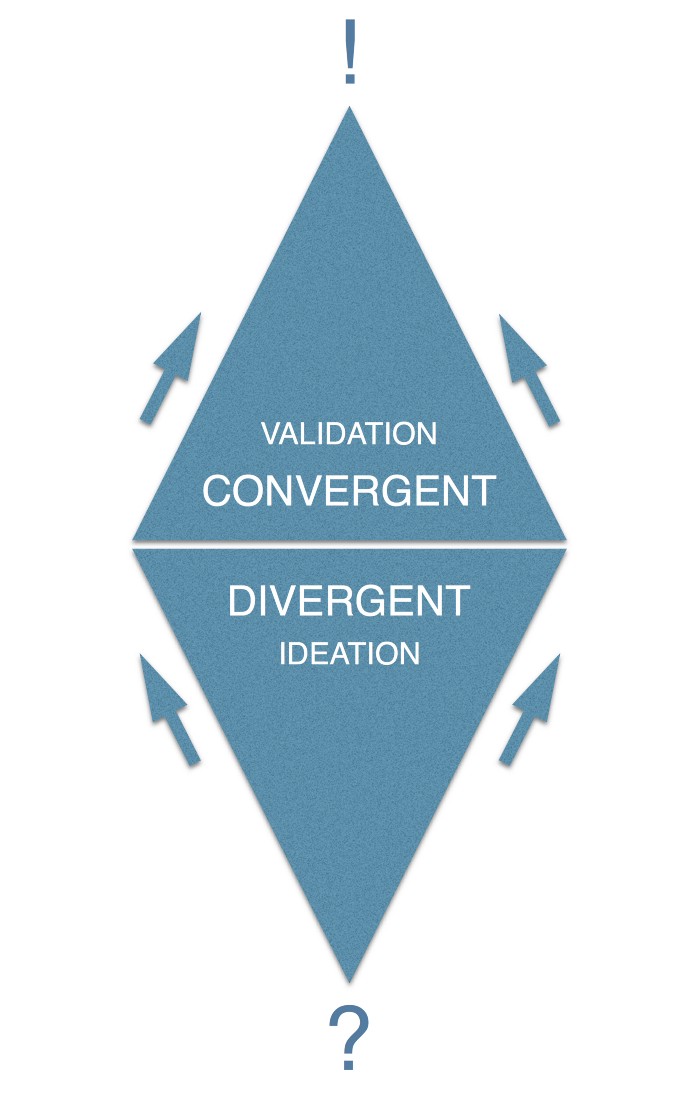

The model was the brainchild of the psychologist J.P. Guilford, an important figure in the history of modern creativity studies. Its basic premise is that creative thinking comprises two styles of cognitive processing: divergent and convergent.

Divergent thinking corresponds to what we variously call right-brain or generative thinking. It is generally abstract, big-picture, intuitive, nonlinear, and inward-focused in nature. It induces us to see things as they could be, rather than as they are.

Convergent thinking is nearly the mirror opposite. Unlike divergent thinking, it is rational, objective, sequential, narrowly focused, highly detailed, and concrete in character. It looks outward rather than inward for answers, such as when we apply the external laws of mathematics to calculate the sum of two plus two, instead of drawing from our imagination.

For Guilford, the creative process is neither one nor the other alone, but both styles working in tandem, and nominally in sequence.

As a linear progression, Guilford’s model translates into a five-stage process composed of the following phases:

- Definition of the problem to be solved: (?).

- A period of divergent thinking, during which you open up your mind to as many ideas for potential solutions as time, budget, energy, or creative capability allow. Brainstorming is a technique for inducing divergent thinking.

- A point of inflection where divergency ceases and convergency begins.

- A period of convergent thinking, during which you narrow down your options to zero in on a potential solution, which is then tested and validated.

- Realization of a final solution: (!).

In real life, of course, the creative process rarely travels in an uninterrupted straight-line trajectory from (?) to (!). More often than not, you find yourself going backwards one or more steps before getting to your goal — if you reach it at all.

But as a conceptual model, Guilford’s paradigm gives a pretty accurate picture of how our minds work in the course of working out feasible solutions to creative problems.